Friday, July 31, 2015

I Don't Feel Welcome in This Country as a Foreign PhD Student: The Government’s Orwellian-Style Monitoring of International Students Makes me Feel Like an Imposter

As a non-EEA (European Economic Area) migrant, if I wish to complete the most mundane paid tasks at the university - such as sealing up undergraduate exam scripts and carrying them from the examination hall to the faculty - I have to fill out seven pages of paperwork.

Each time I complete such a task, I must also fill out an online form requesting that a letter be mailed to my flat, which I then take in person back to the university offices, in order to prove my physical existence in the UK and its correspondence to my address.

Such letters expire every 30 days, so I have had to apply for new ones several times. The last time I was asked to help carry exam papers I refused, on the grounds that it would take longer to fill out the paperwork than to actually do the job.

This week marks the ninth time since I arrived in the UK that I must appear in person at the university registry and display my US passport in order to “confirm my attendance”.

Apparently, it is not enough to the Home Office that I attend a university that is a “highly trusted” sponsor. Or that as a postgraduate tutor I must, ironically, take attendance records of students who attend my classes, as part of the university’s own self-monitoring practices established to retain its “highly trusted” status. Or that I paid several hundred pounds to obtain my Tier 4 visa and residence permit. Or that UK Border Control can track each time I enter and exit the country. Or that I possess a national insurance number and am registered with an NHS surgery. Or that I meet regularly with my supervisors.

In a visa provision that may be eliminated for future international students, I am allowed to work 20 hours a week. I am banned, however, from working as a private tutor. Why? I suppose because some students came to do a course like mine and decided they would set up a tutoring business instead, and were actually quite good at it. So the Home Office says, no more tutoring for you lot. They introduce a blanket policy.

If student migration abuse is a problem, then the Home Office is like a repairman who, when called to fix a hole in the wall, decides to burn down the house.

With the ever-changing goalposts for post-study work visas, we international students find ourselves wondering: even if we got a job offer, would be able to stay in this country? Would we even want to? The idea of deporting students upon graduation, and then inviting them to apply for a job from abroad and re-migrate, is simply laughable as a method to attract the “best and brightest”. As a general principle, the more the rules change, the more trust is eroded.

The Home Office’s continued threats towards international students have created an Orwellian monitoring system that shreds the peace of mind and the sense of stability necessary for critical reflection and groundbreaking research.

Such meddling undermines the mental wellbeing of young persons and mocks the vocation of people who came to this country to use its libraries and laboratories, and to learn.

Here's Why There's No Such Thing as Free Public Education Anymore: The Cost of Classroom Supplies and Mandatory Activity Fees is Soaring Out of Control, and Low-Income Kids are Hurt the Most

| (Photo: BSIP/Getty) |

Staff Writer Liz Dwyer has written about race, parenting, and social justice for several national publications. She was previously education editor at Good.

It’s nearly back-to-school time, which means parents and kids will soon be heading to stores to stock up on all the supplies needed to complete classroom assignments and homework.

But according to the annual Backpack Index from California-based Huntington Bank, the expense of pens and pencils, along with required public school activity fees for the 2015-2016 school year, is increasingly out of reach for cash-strapped families.

The bank crunched the numbers on the cost of supplies and required fees from a representative cross-section of schools in the six states it serves.

According to this year’s index, the parents of an elementary school-age child can expect to fork over $649, a 1% jump since 2014, and a middle-schooler’s family will shell out about $941, up 2.5%. But the moms and dads of high-schoolers will feel the pain in their wallets the most. Supplies and fees for those students will be $1,402, an increase of 9%. Families with a kid in each age bracket can expect to shell out nearly $3,000. That’s a big chunk of change for low- and moderate-income households.

Indeed, a study released last year by the Southern Education Foundation revealed that 51% of public school students are living below the poverty line, which, for a family of four, is $24,250 per year.

Kids whose families are bringing home a little more cash aren’t much better off. A report released by UNICEF last fall found that in 2012, about 32% of children in the United States were living in a home with an income below $31,000. Expecting their parents to fork over 10% or more of their already limited income for public school supplies and fees is just unrealistic.

Thanks to the era of draconian public education budget cuts ushered in by the Great Recession, over the past few years schools have simply passed costs on to families. Since the first Backpack Index was produced in 2007, “the cost of supplies and extracurricular activities has increased 85% for elementary school students, 78% for middle school students and 57% for high school students,” according to the bank.

Indeed, public school parents are no longer being asked to purchase a few notebooks or a $2 box of pencils. Nowadays there are textbook, physical education, and science lab fees. If a family doesn’t pay, the child isn’t prepared to complete assignments and gets a failing grade.

There might be fees to ride the school bus, fees to play on a sports team, or fees for art and music electives. Or if a high school student wants to get on the college track and take an Advanced Placement class, the school might tack on an extra fee to pay for the AP curriculum. Oh, and then there are graduation fees to cover the costs of the commencement ceremony too.

The problem is so out of hand that in 2013 California passed a law prohibiting schools from charging families for supplies, equipment, books, and uniforms. But in the 2014-2015 school year, some parents in the Golden State complained that they were still being charged.

“And this is where I argue that public education is not free,” Nicole Wesley, the principal of Redondo High School in Redondo Beach, California, told KPCC. “We’re not given the amount of funding needed to truly cover all aspects of a high school experience for our students."

If a kid who is already struggling with the effects of poverty and is behind academically is confronted with paying such high costs for school supplies and mandatory fees, that might make dropping out more likely. “We work closely with and in public schools and see that many students cannot afford a backpack or the list of supplies they need to learn," Communities in Schools President Dan Cardinali said in a statement about the Backpack Index.

The nonprofit, which works to combat the dropout rate, is just one organization that holds school supply drives to help eliminate that hurdle for struggling students. "While teachers and many school districts do what they can to help students obtain supplies, we need to do more," said Cardinali.

Communities in Schools affiliates hope to collect enough supplies to meet the needs of 1.5 million public school students. But unless states get serious about funding public education, the problem of districts passing costs on to parents in the form mandatory fees doesn't seem likely to disappear anytime soon.

Thursday, July 30, 2015

The Last Word in Doctoral Writing: Mechanics of Last Sentence Rhetoric

| slideshare.net |

In a recent writing class, we gathered the last sentences of journal articles that participants thought were really strong, and analysed why they seemed to work so well.

This is one group exercise that focuses on the mechanics of language for rhetorical force, something that takes doctoral students into a healthy space as they develop their writing’s style and voice.

Group analysis let us define the rhetorical mechanics of what we liked, and why, so that those in the group could improve final sentences of their own articles. The group included people from STEM and non-STEM disciplines - we were well aware by this stage that there were disciplinary differences in preferences for academic writing style.

I’d reiterated the view that the last sentence of any article, thesis, chapter or bit of formal writing has an important role: farewelling readers in a way that is likable and memorable. Readers should leave an article or chapter convinced of the take home message, and, preferably, impressed enough to want to cite it.

It’s the same idea as at any dinner party: both guests and readers need to be made to feel that they are leaving an event that delivered everything they hoped for and that the author-host has maintained trustworthy control right through to the end.

So what did we like as an inter-disciplinary group? Are there general strategies for meeting reader approval?

Short sentences with short words in them were recommended for their power. Rhetorically, they really did have a sense of finality. One last sentence, ‘Nothing else seems to be on offer’ (Young & Muller, 2014), had a gloomy touch of realism, but also shrewdly suggested that the topic needed more research without rolling out that formulaic suggestion: future research needs to be done. We liked the use of a common truism for the final sentence.

In contrast, another last sentence, to an article that looked back at history to precaution what could go wrong if poor decisions affected the future, met with approval for its large Latinate words in juxtaposition to the nostalgia of ‘lost years’: ‘When the definition of those years becomes lost, the public domain becomes obscured, and the constitutional premise of the law degenerates into obfuscation.’ There’s a poetic, almost rapper, rhythm that had appeal.

We were strongly attracted to sentences using well-chosen verbs with connotative power. We liked ‘New ideas about the mind and brain will redraw our knowledge about autism and will ultimately lead to a better understanding of ourselves’ for its suggestion that knowledge can be drawn, perhaps mapped, especially in relation to something as complex as how the mind works. And we noted the inclusive linking of autism to ‘understanding of ourselves.’

‘Poised’ and ‘pursued’ drew approval for this last sentence: ‘Patient-centred outcomes research is poised to substantially change how clinical questions are asked, how answers are pursued, and how those answers are used’. The contributor of that sentence liked, in her words, ‘the persuasive and goal-directed tone that would have helped some fairly die-hard ‘positivists’ see value in stepping out of their comfort zones!’ We liked the counter-balance between the instability of being ‘poised’ and the massiveness of ‘to substantially change’: a dramatic pivotal moment of consequence makes a good cliff-hanger closure.

The same counterbalance is (perhaps less delicately) expressed in the ‘opportunities’ and ‘challenges’ of the last sentence: ‘These are, in short, the opportunities and challenges of the new’ (Royce, 2015).

Unusual nouns met with approval too: in the following we liked ‘myriads’, and ‘nooks and crannies’: ‘Feminising the economy via the deconstructive move extends this powerful representational politics in a different direction, opening up a myriad of ethical debates in all nooks and crannies of the diverse economy about the kinds of worlds we feminists would like to build’ (Gibson-Graham, 2008, p. 153-155). The hourglass shape of the article, which began with a broad overview of its topic and then narrowed down to the specific research niche, opened out again in this final sentence to return to the broader general context set out in the opening paragraph.

There was general approval for ‘murmurs’ and ‘glimpses’ of what another theoretical positioning might allow. We had noted that conclusions were strong when they linked back to the research question or problem, or to the broad issues raised in the opening paragraph.

Our list of last sentence rhetorical strategies to date, then, coming from a fairly small group, includes:

- Punchy, short, pithy

- Evocative vocabulary

- Rhythmic and rap-like

- Cliff-hanger tension

- Pointing to the future

References

Tom Joyce, Relying on customary practice when the law says ‘no’: justified, safe or simply ‘no go’ The Australian Library Journal, Volume 64, Issue 2, 2015.

Cameron, J. & Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2003) Feminising the Economy: Metaphors, strategies, politics, Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography, 10:2,145-157.

Young, M., & Muller, J. (2014). On the powers of powerful knowledge. In E. Rata and B. Barrett (eds.) Knowledge and the future of the curriculum: International studies in social realism (pp. 41-64). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan.

Royce, T. (2015). Relying on customary practice when the law says ‘no’: Justified, safe or simply ‘no go’? The Australian Library Journal, 64(2), 76-86.

Doing Things Differently: By Embracing the Politics of Higher Education, Academics Can Help Create a Better System

Image credit: SLOW POLITICS by Berliner.Gazette (Flickr, CC BY) |

With higher education in constant flux around the latest assessment exercise, to what extent are academics and administrators ‘hitting the target and missing the point’?

John Turnpenny discusses the critical role of the arts and humanities and the grudging acceptance of the linear-rational model for evidence-based decision-making. He argues that by acknowledging that higher education policy is something we help create, rather than something that is wholly done to us, we can start to make a difference.

There is an ongoing and powerfully important discussion about the state of British higher education, especially the role of the arts and humanities. Marina Warner, Sarah Churchwell and others identify the marginalisation of arts and humanities scholarship, the role of top-down administration, and the ‘marketisation’ of universities.

These contributions reveal bigger challenges to the purpose, vision, direction and administration of higher education. Clearly something is not working.

This article attempts to challenge two important sets of arguments in the debate. But it also attempts to offer some hope, both in taking the debate forward and in laying the ground for doing things differently.

The first set of arguments, to summarise crudely, run along the lines that:

The implication is that there is only one particular way universities can make a significant contribution to public life. What seems to lie behind those arguments is a re-statement of a very old ‘linear-rational’ model of the role of evidence in policy-making: academics generate research, which is then communicated to policy-makers, who then use it directly in their decision-making.

- STEMM [science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine] subjects are the most important because they make a direct contribution to the economy

- The arts, humanities and (to a certain extent) social sciences are an indulgence unless they can be tied to helping STEMM

- Studying humanities will not get you a good job but studying STEMM will

The message is that academics should be ready to answer the questions asked by those in power, but not question the basis of those questions, or encourage thinking about a wider agenda beyond that already set. “You do the number crunching, we’ll do the strategic thinking. Academics should be ‘on tap, not on top’.”

But this fundamentally misunderstands the point and role not just of humanities scholarship, but of academic research in all disciplines. Indeed, the linear-rational model has been comprehensively challenged by several decades of research in public policy analysis, science studies, and human geography.

Longer-term dispersal of ideas into the public realm as a way of generating debate, challenging perceptions and reframing problems is at least as important. Climate change is a good example of a problem that emerged from academics challenging and re-framing the agenda.

Another model of the use of academic knowledge is the ‘political’: knowledge as ammunition to back up political arguments, shore up power relations, delay unwelcome decisions or discredit opponents.

So why is the linear-rational rhetoric so persistent? Partly because it keeps being repeated unchallenged, by research councils, REF guidance, government ministers, the general public, and by academics themselves. If something is repeated enough, people forget there are other ways of understanding.

But it is partly because it suits some people to portray the academic contribution to public life like that. This gives a clue as to why we are having this discussion in the first place. If ‘world-leading’ research means just that - setting the agenda - then ‘four-star’ research should be challenging to read for those in power and authority.

Academics, through research and teaching, explicitly or implicitly challenge the linear-rational model, and also challenge existing interests and accepted norms about authority. They encounter the world of the political use of knowledge, and face strenuous attempts to put them back into the ‘safer’, linear-rational box.

The question ‘how does this play out?’ leads us to the second set of arguments. Again summarising crudely, these run that:

These arguments deliberately foster a certain perception of academics’ motivations, tie them (where no tie is necessarily logical) to a particular style of public management, and develop doubt and division between academics of different disciplines, or the same discipline at different universities. In short, this is politics.

- Academics who object to any policy or practice are simply scared of losing their privilege

- Academics must be closely managed using performance targets

It is taking a legitimate and relatively uncontroversial issue (‘academics should make a significant contribution to public life, and should be accountable for their work’) and making it seem there is only one answer to exactly how. The answer that keeps academics on tap, and not in any danger of being on top.

There has been a detailed, impassioned and inconclusive debate over many decades about what motivates public servants like academics, teachers, police officers, park-keepers, soldiers, Job Centre staff, nurses and fire-fighters.

The idea that all are motivated ultimately by maximising self-interest has been comprehensively challenged by research showing that public service, loyalty and dedication to the aims of the service are vitally important. But if academics are assumed to always be self-interested utility maximisers, this will shape how higher education is administered and run.

Incentives and rewards will assume academics respond to events in a certain way, for example, individual competition for influence, prizes, selection, promotion, and equipment. It can also assume that academics need to be monitored to avoid them maximising their own interests rather than the interests of the ‘principal’.

If academics feel their complex range of motivations are not being heard, or they are forced to behave as if they are motivated by something else, it leads to anger, disillusionment, sullen box-ticking compliance, gaming the system, or simply despair (see Nadine Muller for more on this). Or an underlying sense of guilt and self-doubt.

And since it is easy in any human activity to ‘hit the target and miss the point’ - to try and maximise the target rather than what the target is trying to measure - problems can be painted as a personal failure of individuals rather than a distorted institutional structure, or acknowledged as a piece of deliberate politics.

So what can academics do? It might be seen as awful that academics should be drawn into politics. But everything we do as public servants is political, whether we like it, or recognise it, or not. It is better to embrace our role as political actors. It has benefits. Political actors have influence.

So, how can this influence be best exercised? In a political situation, reasoned arguments like more and better justification and explanation of academic work are not necessarily useful - they may actually make things worse. Taking action to shape higher education policy itself is much more useful. How?

Generally, policies are not just created at high levels and imposed on those further down who have to implement them to the letter. Policy cannot feasibly be made as a set of instructions with every eventuality specified. There is a necessary reliance on large amount of discretion among those at ‘street-level’ as to how policies are carried out.

Police officers on the beat, for example, have a huge influence on how policing policy is implemented, by deciding who to arrest, who to question, and what offences to pursue as priorities. This discretion also shapes and changes the policy itself.

The actions of ‘street-level’ public servants actually help create policy in their specific areas, whether those people recognise it or not. So there is a choice. Academics grudgingly ticking boxes will have some influence on policy, but probably not the desired one. We can do better than that.

By acknowledging that higher education policy is something we help create, rather than something that is wholly done to us, we can start to make a difference. Our detailed response will help shape the future of higher education in the UK.

This piece originally appeared on Eastminster, a global blog about politics from the University of East Anglia (UEA), and is reposted with permission.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

About the Author

Dr. John Turnpenny is a Senior Lecturer in Public Policy at the University of East Anglia. His research focuses on the relationship between evidence and public policy-making, and use of policy analysis tools. He is the co-editor of The Tools of Policy Formulation (Edward Elgar, 2015).

Wednesday, July 29, 2015

How to Survive Your PhD: A Free Course

A year and a half ago, ANU gave me a chance to make a MOOC.

For those of you in the know, a MOOC stands for ‘massive open online

course’. ANU has partnered with EdX, a MOOC delivery platform, so that

thousands of people have the chance to participate in ANU courses from

around the world, for free.

The process of bidding to run a MOOC at ANU is by competitive tender, so I was surprised when I was given special funding to do one. It was an honour to be singled out and ‘jump the queue’ so to speak. It showed that ANU management had pleasing faith in my abilities … Hmmm. Should they really have so much faith?

In less than an hour I had convinced myself that ANU management had made a big mistake. Sure, I had run a successful blog for 5 years - and authored a few online courses - but this was different. I’d never done anything on this scale before. It was sure to be a miserable failure.

It felt like I’d been asked to organise a massive party. What if no-one enrolled? Not only would I fail, but EVERYONE IN THE WORLD WOULD SEE ME FAIL. The whole world would discover what I had known, secretly, for a long time … I am only pretending to be clever and interesting. I am not as good as everyone seems to think I am.

I’ve seen this pattern of thinking, which is called ‘imposter syndrome’, in PhD students many times, but it took me a surprisingly long time to recognise it in me.

After (metaphorically) smacking myself upside the head a few times, I applied the imposter syndrome cure I always recommend to others. I decided to suspend judgment. Just get on with it and worry about if it was any good later. So I tried to write down ideas - any ideas, bad ideas, stupid ideas …

I worked on ideas for nearly a year, but made frustratingly slow progress. I had what golfers call ‘The Yips’ - a sudden and unexplained lack of ability, just when I needed it most. As the Yips dragged on, and on, the fear started to set in. Everything I wrote seemed dumb, boring, pointless. ANU got a bit worried about me for real at this point, and a couple of people were assigned to help.

Talking with generous, open-minded colleagues was just what I needed. Katie and Chris listened to my account of my troubles and encouraged me to see these as the themes for the MOOC. We worked together to re-orientate the MOOC around the effects of emotions on research student performance and eventually (after much debate) called it How to survive your PhD.

The title makes it sound like it’s just for students. While it certainly aimed at you, we think it can be so much more than a normal course that teaches you stuff. We imagined How to survive your PhD as a node in a huge global conversation, where students and supervisors could, together, work to understand the emotional problems that can get in the way of good research progress, find and share new strategies for coping.

We have designed it so that this conversation can spill into other spaces - social media and campus coffee shops; supervisors offices and classrooms. And since we have a massive, global, free platform, why confine it to the university?

We thought mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters and partners might want to join in the conversation too. Many of these people are heavily invested in the success of their loved ones. So we decided to write in plain language to make it accessible to anyone who is genuinely interested in helping PhD students survive and thrive.

As I worked with Kevin Ryland to develop the course content, backed with research sourced from a wide range of literature on emotions, the very problems I had been experiencing started to become modules.

The module on Confidence is all about the imposter syndrome. Why it happens, who tends to suffer from it most and how to combat it. I then wrote about Frustration, particularly why writing is frustrating. Students report that supervisors often give bad feedback - why does this happen when supervisors are themselves expert writers?

My experience of the Yips became a module on Fear. Why do we sometimes fear writing? How can we get over our fear and write anyway? Many people I know are afraid of presenting their research in public - yet can teach a huge class without any problems. What’s all that about?

A module on Confusion was next, which proved to be quite confusing to write. I found myself looking at my own emotional responses in a different way. I did a lot extraneous, perhaps unnecessary, reading. This experience became a module on Curiosity. Curiosity is important to researchers, but it can also be a problem because it’s hard to shut it down once it gets going.

By this time I was nearly half way through the MOOC, but the enormity of the writing and thinking task was getting to me. Hours of writing paralysis at my desk meant I had to I spent many weekends working while my family went out and enjoyed the Canberra sunshine.

I listened to a lot of James Blunt. I ate badly and let my exercise routine slip. I re-experienced Thesis Prison - the feeling of the world going on around you while you are stuck in a room - writing, writing, writing.

This experience eventually was incorporated in the module on Loneliness. Many research students have strong family connections and lots of friends - yet can still feel very alone. Why is the sense of intellectual isolation so intense and so common? Is it just a part of the process, or something we foster deliberately? Is there really anything that others can do to help?

I was grinding through the writing work by now, I could see the light at the end of the tunnel, which (perversely) made me start to lose interest. My heightened attention to my emotional state caused me to critically reflect on my work problems. I love problems. I love researching them and thinking of solutions. But when I have solved the problem, even if just in my mind I’m over it. The next bit, the actual doing, is boring!

Ah - boredom! Of course!

I junked a module on courage and put Boredom in its place. It turned out to be the most enjoyable of all the modules to write. I researched what boredom is and why it happens. I found a whole lot of research on boredom which was anything but boring. I wanted to end on a high note, so I scoped out a module on Love. Then I got stuck again.

Luckily by this time I had enlisted a trusty team of moderators to help me run the MOOC. Steph, Marg, Anna, Jonathon and Kat are all PhD students and so are in touch with the emotions I was exploring on a daily basis. They started to contribute ideas and review the content. We still haven’t finished the last module on Love, but it’s shaping up to be very interesting!

So, are you interested? ‘How to Survive your PhD’ runs for 10 weeks, but it’s designed to be lightweight and easy to manage and should take you no more than an hour a week. We’ll be extending the conversation onto social media so you can participate in a number of different ways.

Research students and supervisors are the main audience and will get the most benefit, but I can imagine that family members and partners, who no doubt have a keen interest in supporting you to finish your research degree, might want to join up too. I’ll be in there chatting with you everyday, along with my team of trusty moderators.

You can sign up for ‘How to survive your PhD’ here.

Or you can watch a video trailer here.

Filming the MOOC was very confronting, and a story in its own right, but here’s a trailer to give you a taste of the content look and feel.

Crucially, unlike other offerings in this space, ANU has made this course completely free. I know that other MOOCs have grown campus communities around them - I’d love it if we could do that with this MOOC too. So why not grab a friend or two and convince them to enrol? It would be a good excuse to grab a coffee once a week and have a chat.

If anyone is a research developer and interested in running it in a formal way, please feel free to email me if you need advice or ideas.

As you can tell from the above, this MOOC extremely hard to write and put it together. I complained about it to everyone who would listen (thanks Twitter!) but I’m glad I did it.

I’m especially glad I had the able assistance of a team of people including Kevin Ryland, Katie Fruend, Nguyen Bui, Chris Blackall and Crystal McLaughlin and top level tactical support from the ANU online team leader Richard Robinson and DVC Marnie Warnes-Harrington. I’m so lucky to have a team of able moderators in Steph, Marg, Anna, Jonathon and Kat. Special thanks to Nigel Palmer who played the role of critical friend so well.

I do hope you’ll think about coming to my MOOC party - and that some of you will invite your parents and partners. I think it will be fun! If you have any questions about the course and how it will run, please feel free to put them in the comments.

Tuesday, July 28, 2015

Research Data: I Only Have Eyes for Excel

by Research Whisper: https://theresearchwhisperer.wordpress.com/2015/07/28/i-only-have-eyes-for-excel/#more-3783

by Research Whisper: https://theresearchwhisperer.wordpress.com/2015/07/28/i-only-have-eyes-for-excel/#more-3783 Jonathan Laskovsky is the Senior Coordinator, Research Partnerships in the College of Design and Social Context at RMIT University. He is primarily responsible for managing research partnerships support and administration within the College.

Alongside this role, Jonathan has research interests in modern and postmodern literature with a particular focus on fictional space and critical theory. He tweets as @JLaskovsky and can be found on Linkedin.

Data is increasingly part of our lives. This isn’t surprising when you consider that networking giant Cisco has predicted that the data centre traffic alone in 2018 hit 8.6 Zetabytes. That’s 8.6 trillion gigabytes, or enough to cover 119 trillion hours of streaming music. Enough for 22 months for every single person on the planet in 2018!

We are increasingly exposed to data in research as well. Think about digital humanities, for example. This means that we increasingly need better ways to display, interpret, and analyse it.

What we are really talking about here is Data Visualisation (DataViz). In a world of big data, the importance of good DataViz cannot be underestimated. This applies along the entire spectrum of research, from grant applications to reports to journal articles. Or at least it should.

In my job, I often see project descriptions of concise, tightly written prose. Succinct, well-structured arguments that outline in crisp sentences what the research is about, and clearly identify roles and responsibilities in measured, orderly terms. Then there is a often a table.

Usually, this table is outlining either data discussed within the proposal, or showing the project timeline with milestones, and staff markers and outputs, etc. This table is almost always hideous.

Let me be clear: often, this is not always entirely the fault of the author. Microsoft Word deserves a special place in hell for its table tool. A special burning place with sharp pointy things. It deserves this because, for a product that has been around for over 30 years across three platforms, it still doesn’t include a decent table tool. That’s right, everyone - there was an Atari version of Microsoft Word (for those of use who can remember when Atari made computers …). Really, though, Word is not what you want to fall in love with.

When it comes to data, you should only have eyes for Excel, which is Word’s smarter, slightly nerdy sibling. Excel is your friend. This is because, unlike Word, Excel treats your data with respect. Excel would totally call you the next day. More importantly, it’s a program designed specifically to handle and process data (yes, there are other programs such as R and Python, but let’s walk before we run).

This means you can create incredibly powerful formulas with it. These range from complex, nested ‘if’-statements, to simply having columns that automatically add up your budget items so your total is actually the sum of the numbers in them. Trust me when I tell you that this doesn’t always happen, especially when you create your budget in Word.

Yet, using Excel is only half the picture. Don’t just take my word for it - listen to the expert. Stephanie Evergreen introduced me to the wonderful world of DataViz. I attended a presentation she gave that completely changed my approach to Excel, as well as my approach to presenting data in general.

Listening to Stephanie talk for just one hour had me convinced of not only the importance of DataViz, but also its relevance and importance in the world of research. Three of Stephanie’s points really stuck with me:

1. Humans absorb information visually,

2. Poor DataViz obscures your argument, so

3. Using DataViz well increases the effectiveness of your argument

These are really important points and apply to the entire gamut of research outputs from theses, to conference presentations, to papers and books. Let’s look at them in a little more detail.

1. Humans read visually (or charts vs tables)

First, columns that add up are a great start (believe me), but a cramped table full of figures is hard to read, hard to connect to your argument, and can potentially frustrate the reader. Remember, whether you’re submitting a journal article or grant proposal, frustrating the reader this is the last thing you want to do.

This means we need to ask whether a table is really the most effective way to present the data. The answer is probably not. By all means, include the figures in an appendix, but a chart is often a better option because humans process visual information more easily than they do numerical (.pdf - Evergreen’s PhD thesis).

2. Poor DataViz can obscure (choose wisely)

“Aha! So, I just put everything into a chart right?” Well, not really. A chart is often helpful but it’s not a silver bullet. I love Excel but its defaults are generally agreed to be awful from a DataViz perspective.

From dull or bizarre colour schemes to overly complicated 3D charts, Excel can present the user with too many options. Most of them will over-complicate what you are trying to present, and detract from your point. Data art is a perfect example of this - it looks pretty, but do you really have any idea what message this chart is trying to convey?

Exactly (it is a map of the internet made in the 1990s, printed in Wired magazine). It can happen in the everyday as well, though. Look at the chart at the top of this post. Something very exciting is happening with the yellow column, but this chart renders it almost impossible to tell anything about the rest.

The scale is thrown off completely by that immense column and it makes the rest of the chart effectively meaningless. And this brings me to Stephanie’s third point.

3. Good DataViz strengthens your point

The principles used to create good DataViz apply to all forms. A well-crafted table can show clearly how milestones and tasks relate to each other. A thoughtfully constructed Gantt chart can communicate how activity and outputs will map out across time (what is a Gantt chart, you ask?). A carefully built chart can emphatically drive your point home.

——————————–

So, how do we learn good DataViz habits?

Well, a few tips I’ve gleaned from Stephanie are: keep it simple and use colour to only highlight the point you want the chart to make. Get rid of anything 3D and, remember, pie charts are among the hardest for humans to process. Stephanie’s blog outlines all of these points (and many more) in full detail and is well worth a visit.

Like it or not, data is here to stay. Avoid it at your peril. It may not define your field, but you cannot avoid interacting with it. Learning how to use it well will only enhance the impact of your research.

Best of all, thanks to people like Evergreen, learning how to use it well is now easier than ever. Take a little time to engage with it, and I guarantee you that you too, will only have eyes for Excel.

Monday, July 27, 2015

Qualitative Data Analysis: Video Series

| Rasch.org |

ATTENTION: MORE VIDEOS IN THE SERIES WILL BE ADDED TO THIS POST OVER COMING WEEKS

This post will provide links to a videos that form a series that I hope will help people grappling with the many challenges of analysing qualitative data. Analysis is, to me, by far the hardest but also most rewarding part of research.

One thing I have learned over the many years is that there are no short cuts! Good analysis has to take time. Lots of time. Time with your data. So you won’t find tips and strategies for a quick outcome or cutting corners.

I have tried to focus on ideas that are relatively simple to grasp but profound in their implications, while avoiding areas that are covered extensively in textbooks and methods literature. The videos are relatively short, and I will embed pictures of any slides that appear in the videos here.

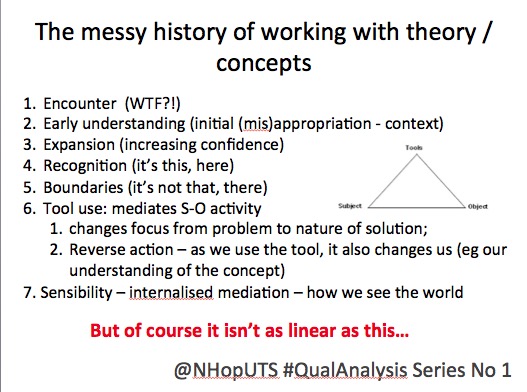

Video 1: The messy history of working with concepts or theory in qualitative analysis

You can view qual analysis video 1 on youtube.

I chose this one first because it sets the scene for a process that is focused on you, the analyst, and how concepts or theoretical ideas can change what you can see in and do with your data. It doesn’t get into technical ideas about processes of applying theory. Instead it talks through what I have experienced many times now in the hard slog of coming to understand a concept, what it can do for you and what you can do with it in a particular project.

Here is the slide:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)