by Thesis Whisperer: https://thesiswhisperer.com/2020/12/23/the-year-of-living-covidly/

|

| Image: economist.com |

We made it. 2020 is about to be over.

Before a year in review post, a special announcement:

As regular readers know, for over 10 years now I have run the Thesis Whisperer blog as a ‘not for loss’ model, where I donate excess above operating costs to charity.

This year, as an explicit christmas fundraising project, I have packaged all my 2020 ‘Covid Diary’ blog posts – just on 30,000 words of them – into a new ebook. Each post starts with some notes about what inspired the work, or how it was received. I’ve also included a ‘bonus’ unpublished piece of writing that the NTEU magazine rejected for political reasons, a foreward and afterward reflecting on the year.

I’m selling this ebook for the low price of $4 AUD – the cost of a cup coffee. I will donate all proceeds of this ebook to the UN Women’s ‘Restoring Dignity’ project.

You can buy the ebook, as a PDF, directly from the Thesis Whisperer site here.

Each $20 raised goes towards a pack containing basic sanitary supplies to women experiencing crisis. Giving a pack with some undies and a toothbrush sounds like such a little thing, but it matters. Imagine having your period with no tampons to be found, or not being able to brush your teeth after a disaster has left your city with no power? Or worse – being stuck in a refugee camp where such items can only be purchased at great cost. I’m grateful to UN women for running initiatives like this. I believe small, thoughtful, concrete actions are the way to build a better world for everyone and I’m proud to be able to support their efforts.

I think this ebook contains some of my very best writing. Covid has been terrible, but weirdly good for me creatively. I’ve included a ‘bonus track’ – which is a piece that the NTEU newsletter refused to publish for political reasons. I’ve been wanting to share that story and this seems like a good place to do it.

I hope you will think about purchasing the ebook and supporting this good cause. I’ll report back on the number of dignity packs we were able to donate early next year.

Now we have the Christmas fund raiser out of the way, I am going to indulge myself with a post looking back on this extraodinary year.

2020 started with smoke and fire, then freak hailstorms, and finally the first pandemic in 100 years. I am extremely grateful to still be standing at the end of it all. Sure, I’m on anti-anxiety meds now and I gained about 15 kgs, but better things are appearing on the horizon with the development of vaccines.

While the whole year felt like walking through mud – and stinky mud at that – it was actually a fruitful here at ANU. My team – the wonderful Victoria Firth-Smith and Cally Guerin – have been towers of strength, ably assisted by Hannah James and Nic Baldovich. Words fail to express my gratitude, especially for how you picked up the pieces when I had a mini break down right at the start of the first lockdown.

My research collaboration with Will Grant and Hanna Suominen on using machine learning to explore the post PhD job market is about to go into the 5th year. Between us we have given nearly 40 presentations of ‘So, you’re graduating your PhD in a Pandemic – what’s next?’ at various universities in Australia and around the world. It’s been a labour of love turning our algorithmic, machine learning research on job advertisements into PostAc: a tool that can help people wanting to leave academia (available by university subscription only).

I realised a long term ambition when I started a podcast called ‘On the Reg’ with my good friend Jason Downs; pleasingly, it’s already had over 4000 downloads by people interested in how to be productive in academia, without over-working. In November I helped run a four day online event called Whisperfest with my good friends Tseen and Jonathan from the Research Whisperer and Narelle Lemon from The Wellbeing Whisperer. It’s fair to say Whisperfest was much more successful than we dreamed. We’re producing a podcast of the series and already talking about how we might keep working together on a more ongoing basis.

While I pursued all kinds of collaborations this year, I returned Thesis Whisperer back into a solo project.

After 10 years of editing guest posts, and dealing with reams of correspondance, I was exhausted. I thought about quitting blogging altogether, but I realised I love writing here. I thought long and hard about how to find the joy again. At the end of last year, I drastically changed my editorial model and stopped publishing guest posts.

This year I gave myself the luxury of only posting once a month. I also turned the comments off, which was more of a mental health move than an editorial one. I didn’t feel like I could give them enough attention and care while I was recovering from a break down myself. I was rewarded with increased readership and at least one post that went mildly viral.

Thank you for all the lovely feedback via email and on the socials. The best place to talk to me is still Twitter – @thesiswhisperer.

I surprised myself a bit by writing up a storm this year – nearly 30,000 words on the Thesis Whisperer alone. I re-released a new version of Tame Your PhD, with a lovely new cover: you can find pictures of the new paperback version and where to purchase it here.

I surprised myself a bit by writing up a storm this year – nearly 30,000 words on the Thesis Whisperer alone. I re-released a new version of Tame Your PhD, with a lovely new cover: you can find pictures of the new paperback version and where to purchase it here.

I also finished another book with my good friends Katherine Firth and Shaun Lehmann: ‘Level up your essays’ is aimed at undergraduates and will be out early next year through New South Press. I hope some of you will find it useful in your teaching practice. For the first time in about seven years I don’t have an active book contract underway, but I have a few promising irons in the fire, don’t worry!

Finally, ANU have recognised all my hard work and contributions with a promotion to full Professor, which takes effect on the 1st of January.

You can listen to me talk to my Pod co-host Jason Downs about my way of demonstrating impact here (about 6 minutes in because that’s how we roll :-). I want to take this opportunity to thank them for being a supportive employer who really get how I am trying to make a difference in the world.

I hope the Thesis Whisperer has provided some good advice and the occasional laugh in this somewhat bleak year. I wish a peaceful, non-infectious holiday period for those who have a break coming up. I look forward to 2021 being the real start of the roaring 20s!

I’ll be back with a new post in February next year.

In solidarity,

Inger

Canberra, 6th of December.

If you want to help me continue the work in 2021, here’s a page of ways you can contribute.

If you want to purchase my UN Women fundraising book, go here: You can buy the ebook, as a PDF, directly from the Thesis Whisperer site here.

If you want to read all the 2020 posts without purchasing the ebook here’s a list:

You have to believe what you do matters

Should you quit (go part time or pause) your PhD during Covid?

The valley of deep Covid Shit

Where I call bullshit on how we do the PhD

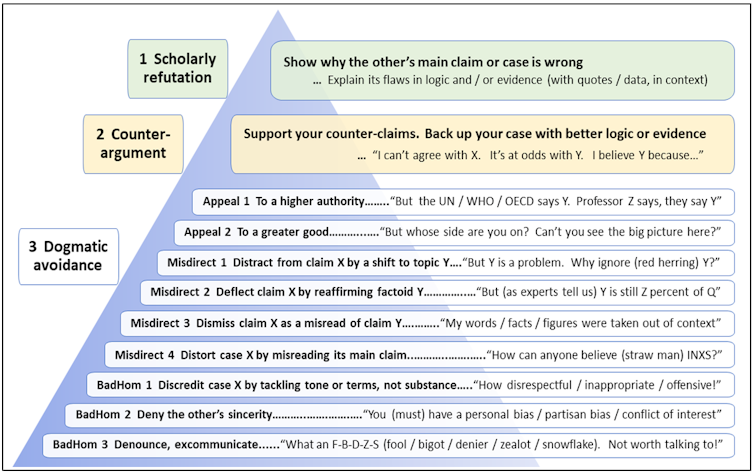

Why academic writing sucks, and how to fix it

How NOT to be an academic asshole during Covid

Rich academic, poor academic: making an academic living in Covid times

Do you need clown shoes? Finding a research job in Covid times

Imposter Syndrome doesn’t exist, but I call mine Beryl

While you scream inside your heart, please keep working