by Christopher L. Diamond and Trent Brown, The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/6-unis-had-hindi-programs-soon-there-could-be-only-1-and-thats-not-in-australias-best-interests-151096

La Trobe University is in talks to discontinue its Hindi program, along with Greek and Indonesian. In the mid-1990s, six Australian universities taught Hindi. If La Trobe ends its program, Australia will be left with just one university (ANU in Canberra) that teaches Hindi.

This would be a significant setback for Hindi in Australia. The decision reflects a COVID-induced budget crunch at La Trobe, but also a long-term decline in the study of Asian languages in Australia.

Good relations with India are vital

Hindi’s decline may seem strange, since it’s the official language of India, with more than half-a-billion speakers. Australians have a growing interest in India and connections between Australian and Indian universities are increasing.

Given the current tensions with China, Australia’s relationship with India – and other large Asian nations – has never been more important.

Even before the feud with China, the benefits of improving the Australia-India relationship were widely acknowledged. Australia and India have converging geostrategic interests. There is tremendous potential for mutual benefit by enhancing economic, social and cultural ties.

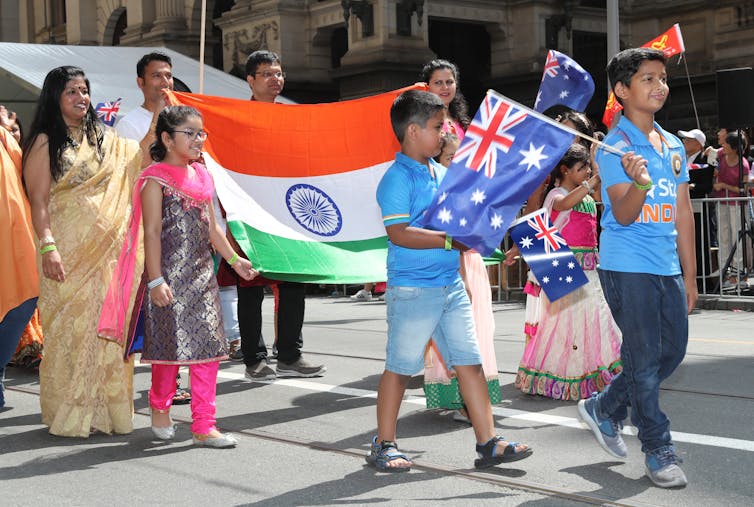

Here in Australia, the Indian diaspora is large, numbering around 660,000, and growing fast.

In the 2016 census, Hindi was among the fastest-growing languages in Australia. A closely related language, Punjabi, was the fastest-growing.

Community enthusiasm for Hindi is reflected in more than 2,400 community members signing a petition to save the La Trobe program.

Language helps bridge diplomatic gaps

In 2018, University of Queensland chancellor Peter Varghese, a former senior diplomat and public servant, released his government-commissioned India Economic Strategy to 2035. This report sought to guide Australia’s engagement with India for years to come.

Varghese noted Australia has struggled to match its enthusiasm for India with substantive engagement. Efforts to establish connections often fall short due to failures of mutual understanding.

The report argues “people-to-people” links between Australia and India will be as important as political linkages. They will help shape perceptions and foster mutual understanding in ways political delegations could never do.

Varghese was not alone. The Victoria government’s 2019 India Strategy made its first priority to “celebrate and strengthen our personal connections”.

Most recently, the 2020 joint statement on a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between Australia and India, signed by their prime ministers, Scott Morrison and Narendra Modi, gives people-to-people connections a prominent place in “enriching all aspects of bilateral ties”.

Government talk of “people-to-people connection” has not been followed up with support for this goal. In particular, support for language programs has languished.

Classes foster people-to-people connections

Language education cultivates people-to-people connections. These personal connections start from the very first day of a language class.

Hindi classrooms in Australia have immediate positive effects for Australian students and society. Students are immersed in a complex of perspectives that reflect life in all parts of South Asia and in global diaspora communities.

Hindi language teachers capitalise on the bicultural experiences of students with South Asian heritage. These students are already experts in negotiating a relationship between Indian and Australian cultures. These skills make our students the best ambassadors for Australia in the “nooks” of Indian life that evade official state actors.

Equal contributors to our classrooms are non-heritage students who enrol in tertiary-level Hindi courses because of their personal interest in South Asia. Together, heritage and non-heritage students negotiate learning Hindi and understanding Indian culture. They form lasting friendships that deepen the ways in which Australians of many different backgrounds understand each other.

Cultivating culturally literate Indian-Australian and non-Indian-Australian speakers of Hindi depends on providing a learning environment that is found only in university classrooms.

La Trobe’s proposal, by halving the national university-level Hindi teaching capacity, would also undermine our capacity for building human connections between India and Australia.

A blow to the local Hindi ecosystem

University-level Hindi programs form part of larger language ecosystems. They depend on thriving primary and high school programs. This ensures a supply of Hindi students and educators at all levels.

In Melbourne, a Hindi language ecosystem was just starting to take root. Two schools, Rangebrook Primary and The Grange College, now offer Hindi as their main language other than English. A number of energetic informal networks and societies focus on Hindi language and literature.

La Trobe’s Hindi conferences and events have been an important focal point for these groups over a number of years.

The loss of the La Trobe program is thus not only a blow to students wishing to study Hindi at a university level, but also to this entire emerging Hindi language ecosystem.

While dynamic and engaging curriculums are needed to ensure sustainable Hindi programs at Australian universities, they are not enough on their own. There must also be sustained government support for establishing Hindi ecosystems in clusters around these universities.

One of us made this point in a co-authored policy brief published in 2018. It echoes commentary by others on the decline of Hindi education in Australia since the mid-1990s. Current events in Australia and in the Indo-Pacific should make it clear why we need to reverse this trend.