by Jackie Walsh, Middle Web: https://www.middleweb.com/37934/could-doubt-be-a-tool-to-spark-student-learning/

by Jackie Walsh, Middle Web: https://www.middleweb.com/37934/could-doubt-be-a-tool-to-spark-student-learning/

How might raising doubts in our students’ minds work in a teacher’s favor?

While perusing my Twitter feed several months ago, I stumbled across this claim, attributed to Nobel Prize winning physicist Richard Feynman.

Doubt raises personal questions which are the best catalysts for meaningful discussions.

Feynman’s coupling of doubt with discussion resonated with me and called to mind another author’s view – one specifically related to classroom discussion: “The point of entry into inquiry is the raising of doubt about subjects and issues that the learners care about” (McCann, 2014).

Thomas McCann’s statement, in Transforming Talk into Text: Argument Writing, Inquiry, and Discussion, Grades 6-12, had prompted me to think of the teacher’s role in using doubt to design meaningful discussion. Feynman’s assertion caused me to refocus and ponder the nature, sources, and conditions for student-initiated discussion.

Argument or Collaborative Inquiry?

Meaningful discussions emerging from student doubt take multiple forms, which promote different academic purposes. Broadly speaking, we can sort these into two categories: debate, characterized by a student’s adoption and argument for one selected point of view, and collaborative inquiry, during which students build upon one another’s ideas in an attempt to clarify understandings and arrive at a shared and new or expanded way of thinking.

Regardless of the instructional purpose, discussion is a powerful strategy for student engagement and learning, one of the strongest influences on student achievement (Hattie, 2012).

Discussions characterized by argumentation typically emerge from student skepticism about the credibility or plausibility of an assertion or claim, whether it be an accepted interpretation, custom, practice, or principle or a position or argument made by a classmate or the teacher.

Let’s imagine a discussion that grows out of a student questioning whether The Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution is as relevant today as when it was ratified. Or, a debate originating in one student’s challenge of a peer’s view on whether the long-term benefits of artificial intelligence outweigh the risks.

Such doubt-driven questions ignite student interest and can be springboards to class discussions that enable students to think critically about their personal stance on an issue while engaging in deep learning. These types of discussions, when pursued skillfully and respectfully, serve as practice fields for citizens and are needed to preserve, protect, and advance our democratic institutions.

While some doubts stem from skepticism, others are born out of uncertainty. Consider an elementary student who uses an algorithm to solve a problem, but wonders how division by a fraction can yield a higher number. Or, a foreign language student questioning appropriate usage of formal pronouns.

When a “correct” answer doesn’t ring true to students, the opportunity to surface, discuss, and resolve doubts leads to true learning, which rote acceptance of an expert’s statement may not. In such settings, teachers can harness individual doubt to launch a shared inquiry that results in more substantive learning for all.

Other occasions for collaborative inquiry stem from more open-ended wonderings. For example, a class might question why so few Americans exercise their right to vote and build upon one another’s thinking in an attempt to generate a menu of possible causes and solutions, perhaps utilizing Warren Berger’s (2014) Why?/What If?/How? Sequence to move their thinking forward.

Unfortunately, discussion – whether argumentative or collaborative in nature – is mostly missing from our classrooms.” – Walsh & Sattes, 2015

Unfortunately, discussion – whether argumentative or collaborative in nature – is mostly missing from our classrooms, comprising on average only about 3-5% of total instructional time across all grade levels, K-12 (Walsh & Sattes, 2015).

This is unfortunate given what we know about discussion’s potential for student engagement and impact on learning. The research on the frequency and impact of discussion focuses primarily upon teacher-initiated discussion – not upon that occasioned by student doubts and wonderings. Wouldn’t it be interesting to know how often this kind of discussion occurs in our classrooms?

Conditions Supporting Doubt-Driven Discussion

In many classrooms, students are not comfortable expressing doubts and raising questions that catalyze and sustain discussion. Given my passion for discussion, I continue to ponder, How can we create the conditions in our classrooms that invite students to voice doubt, disagreement, and wondering and use these as springboards to thoughtful discussion?

While acknowledging that conditions may vary by grade level, academic content, and student characteristics, my experience in K-12 classrooms suggests at least four ingredients interact to create the conditions which nurture discussions fueled by doubt and personal questions:

- Teacher Mindset,

- Classroom Culture,

- Teaching Modeling, and

- Student Skills and Dispositions.

These four can serve as guides for reflection and decision-making for those who seek to advance student motivation and ability to inquire deeply into issues and topics that matter to them.

Teacher Mindset

Student-initiated discussion cannot occur absent teacher openness to student expressions of doubt and uncertainty. Teachers must encourage student questions and dialogue. Because of issues related to control – including curriculum pacing/coverage and behavior management – many teachers grapple with the feasibility of this student-centered approach.

Reflection on one’s personal beliefs about learning and teaching is a first step to transforming classrooms into places where students partner in driving the learning. How do you deal with the following dichotomies that confront teachers in multiple ways, multiple times throughout a school day?

- Deep Understanding or Right Answers

- Commitment or Compliance

- Flexibility or Control

- Openness or Certainty

- Interpretation or Evaluation

- Questions or Answers

Our thinking about these dichotomies feed into the mindsets that affect our acceptance of student-driven dialogue.

A Safe and Inviting Classroom Culture

Psychological safety is the cornerstone of a learning culture in which students are willing to voice doubts, raise questions that are counter to a stated position, or propose a different way of viewing an issue. In such an environment, respect trumps ridicule, trust replaces skepticism, relationships are cultivated and valued, diversity is celebrated, and a caring community supports each individual.

How do we go about creating such learning spaces? We can begin by reflecting on and developing actions in response to the following:

- In what ways are we orchestrating opportunities for students to develop trusting, respectful relationships with their peers?

- How are we clarifying expectations related to engagement in dialogue, including equitable participation, listening to understand other’s perspectives, voicing of one’s own thinking (rather than mimicking the thoughts of others), and developing comfort with silence?

- What are we doing to cultivate a community of inquiry by moving away from an emphasis on “right” answers to a valuing of where students are in their thinking and learning?

Left to their own devices, students will determine the chemistry of a classroom, whether it be nurturing and inviting to all, or destructive and discouraging to some. Our job is to intentionally envision a culture that we can co-create with each class of students and intentionally design experiences that mobilize students in this endeavor.

Teacher Modeling

When we demonstrate expected norms and behaviors, we are using the most powerful of all teaching tools. By explicitly expressing our own uncertainty, accepting ambiguity, respecting differences, and raising personal doubts, we are nurturing norms that support doubt-driven discussion. Specific strategies teachers can use to promote this end include:

- Engaging in think-alouds through which we make visible to students the what and why of our own thinking;

- Honoring silence as a time for all to grapple with internal conflict, to process another’s perspective, or to form a question or comment to share publicly.

- Asking personal questions that emerge spontaneously, questions that express doubt or uncertainty about the issue or topic under discussion.

- Expressing comfort with not knowing, or with a lack of certainty; moving beyond a search for “the right answer.”

- Withholding evaluative comments about students’ statements while posing questions to better understand an individual speaker’s thinking, as appropriate.

Our modeling actually begins with the questions we prepare in advance of a lesson to focus student learning on standards and learning targets. These communicate our expectations about thinking and learning. Do our questions serve as gateways to student doubt and discussion, or do they serve to march students through the curriculum in a lock-step manner? If students are to invest emotional and intellectual energy into challenging their own and others’ thinking, our prompts must evoke curiosity, cognitive dissonance, or uncertainty.

Such prompts are not only open-ended, but also provocative enough to ignite student interest. Students find personal importance in the subject of these questions. These initial teacher questions incite student wondering and doubt that extend and sustain discussion.

Our modeling cannot be effective without complementary mindsets. Unless our behaviors align with our beliefs, students will not perceive them to be authentic. And, if we have not reflected deeply on our beliefs and mindsets, we are unlikely to be consistent in our demonstration of dispositions and behaviors that we desire our students adopt.

Student Skills and Dispositions

The previous three ingredients – teacher mindset, a safe and inviting classroom culture, and teacher modeling – are necessary, but not sufficient, to students’ raising doubts that lead to discussion. If individual students are to pose questions that fuel the thinking of their classmates, they must possess both the skill and the will to do so. If they are to engage in respectful discussion with peers, they must adopt the norms and develop the skills of respect.

While some students seem to arrive in our classrooms with these skills, others struggle to orally express their doubts and uncertainties. We can help students develop these skills by providing them with stems to use and affording them opportunities for practice. Among simple – and respectful – stems to use in expressing doubt are: I’d like to offer a different way of thinking about . . . What evidence supports this position? I’m wondering why . . . ? What if . .?

Oftentimes, students’ dispositions are greater barriers to their participation than are their skills. They may lack confidence or be risk averse; seek answers rather than surface their own questions; accept claims without evidence; seek reinforcement for their thinking rather than broadening their understanding; value competition over cooperation; and suppress doubts and uncertainty when those bubble up.

Teachers cannot dictate dispositions. We can, however, be explicit in naming these dispositions and encourage students to reflect on and examine these habits of mind that support personal ownership and self-direction of learning.

More Questions Than Answers

How do we decide which student doubts and questions merit extended discussion? At what point do we cut off student talk and bring closure? How can we develop all students as questioners rather than deferring to the more proactive? When do we allow these discussions to occur spontaneously rather than defer them to a future time (thereby allowing for planning and student preparation)?

These are but a few of the questions I have as I continue my thought journey inspired by Feynman’s observation – a journey that is both fascinating and, I believe, important. This is an instance in which I agree with another of Feynman’s opinions: “I would rather have questions that can’t be answered than answers that can’t be questioned.”

References

Berger, W. (2014). A more beautiful question: The power of inquiry to spark breakthrough ideas. New York: Bloomsbury.

Feynman, R. (2018). Surely you’re joking, Mr. Feynman: Adventures of a curious character. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. New York: Routledge.

McCann, T. (2014) Transforming Talk Into Text: Argument Writing, Inquiry, and Discussion, Grades 6-12: Teachers College Press/National Writing Project

____________________

Dr. Jackie Walsh is the co-author with Beth D. Sattes of the bestselling Quality Questioning: Research-Based Practice to Engage Every Learner, 2nd Edition (Corwin, 2017) and Questioning for Classroom Discussion: Purposeful Speaking, Engaged Listening, Deep Thinking (ASCD, 2015). She is also lead consultant to the Alabama Best Practices Center where she designs and facilitates professional learning for ABPC’s statewide educator collaboratives and for the Alabama Instructional Partners Network. She lives in Montgomery, AL. Contact Jackie at walshja@aol.com and follow her on Twitter @Question2Think.

Dr. Jackie Walsh is the co-author with Beth D. Sattes of the bestselling Quality Questioning: Research-Based Practice to Engage Every Learner, 2nd Edition (Corwin, 2017) and Questioning for Classroom Discussion: Purposeful Speaking, Engaged Listening, Deep Thinking (ASCD, 2015). She is also lead consultant to the Alabama Best Practices Center where she designs and facilitates professional learning for ABPC’s statewide educator collaboratives and for the Alabama Instructional Partners Network. She lives in Montgomery, AL. Contact Jackie at walshja@aol.com and follow her on Twitter @Question2Think.

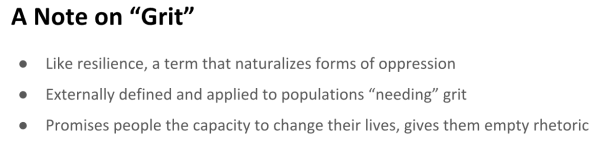

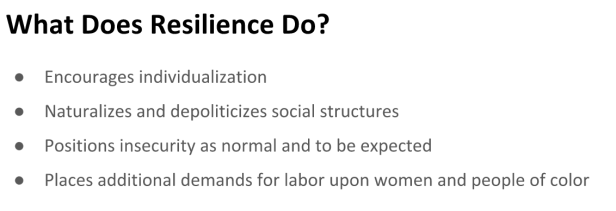

challenges, related to precarious employment contacts, housing and career prospects. There are many

challenges, related to precarious employment contacts, housing and career prospects. There are many  complexities of success or failure as well as the apparently personal attributes that influence either outcome. As Alfie Kohn argues addressing the possible pitfalls of the unquestioning promotion of the ‘

complexities of success or failure as well as the apparently personal attributes that influence either outcome. As Alfie Kohn argues addressing the possible pitfalls of the unquestioning promotion of the ‘

*The authors are not against employability. Both having had experience of unemployment, and are acutely aware that students will be facing realities where they need to demonstrate their employability. Our reluctance to be gung-ho advocates of resilience is also drawn from a need to be open about the current economic environment and the opportunities available. Even if a student has the right attitude, mindset and toughness, this is no guarantee of success. Further, having “the right attitude, mindset and toughness” is not an authentic set of tangible outcomes to demonstrate to an employer. They are not like, say, actual skills.

*The authors are not against employability. Both having had experience of unemployment, and are acutely aware that students will be facing realities where they need to demonstrate their employability. Our reluctance to be gung-ho advocates of resilience is also drawn from a need to be open about the current economic environment and the opportunities available. Even if a student has the right attitude, mindset and toughness, this is no guarantee of success. Further, having “the right attitude, mindset and toughness” is not an authentic set of tangible outcomes to demonstrate to an employer. They are not like, say, actual skills.