You often hear writing described as a skill. And a skill is the capacity to do something well, to use expertise built up through practice. Skills are often seen as merely technical, but a skill requires specialist knowledge and often years of training. However, it’s the capacity/ability to apply and use that knowledge that matters.

We often think that skills are only needed for working with things – but the term skill equally applies to areas such as the cognitive and interpersonal. However, I am not convinced that it is particularly helpful to think of writing as a skill. Yes, writing needs know-how and technique. But skills-talk about academic writing usually lapses into discussions of secretarial matters – the correct use of grammar and syntax for instance, or the ability to edit your own work. Reductive skills-talk in turn easily leads on to conversations about remedial support and better supervision.

When I start to talk with new PhDers about writing I usually avoid focusing on skills and talk instead about three important characteristics of academic writing…

1. Academic writing is a social practice

When writing researchers talk about writing as a social practice they/we mean that all forms of academic writing are produced in, and framed by, disciplinary, institutional and cultural relations, norms and rules. This is a bit of a mouthful. But essentially, for PhDers this means that what you write isn’t a matter of free choice. The university, where you are located and your discipline all shape the writing you do.

So part of the work of the PhD is to learn what these norms, rules and expectations are. Understanding the genres and codes that shape how academic texts are produced is part and parcel of the doctorate.

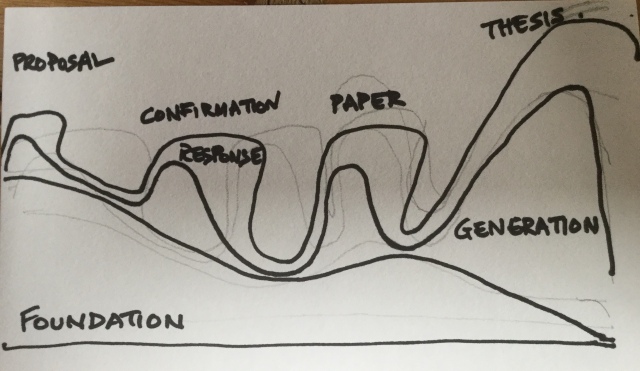

During the doctorate you will probably get to work on a range of academic texts – thesis, journal articles, conference papers, academic posters, blog posts, reports – as well as accompanying texts like bio-notes. You will also develop and build your own noting and recording system. And these all have their own conventions you’ll need to follow.

You do have some choice in how to write of course. You may decide to bend some academic writing conventions – for example you might engage with a range of narrative forms including fiction, performance, poetry and still and moving image. These are all now used as a means of presenting academic discussion and empirical research, so it’s not completely outlandish to stray into these text types.

2. Deep understandings about academic writing support you to write well

I think about writing as a craft that works from and with imagination and realised through connoisseur knowledges and artisan practices.The dictionary defines a connoisseur is someone who knows a lot about a particular topic – the arts, food, wine – and who can judge quality and skill in that particular area.

To be a connoisseur of academic writing means having a deep, and always growing, critical understanding of writing – genres, tools and techniques, histories, debates and traditions. A connoisseur builds a working knowledge of what they consider to be good/bad writing. They can explain to themselves and to others the criteria they use to make such judgements. A connoisseur of writing is able to use their understandings to evaluate their own work, to diagnose problems and to develop strategies that will help them to write ‘better’.

Becoming a connoisseur of any form of writing relies on lots of systematic reading, and on deliberate analysis of that reading. For PhDers, building depth of connoisseur knowledge means not simply reading for content, but also analysing what you are reading. Just as in other areas of your research, like methods, it’s helpful to read about writing. Writing research offers a language and theorised categories through which you can conduct your own analysis. You grow the habit of asking yourself why you think what you are reading is good or bad – what is it about the text that impresses or disappoints?

3. Writing muscles benefit from regular exercise

But why an artisan? The dictionary defines an artisan as someone who is highly skilled in a particular trade – they make by hand and with specialist tools. The artisan produces unique or a limited run of items, unlike a craftsperson who is generally engaged in a form of mass production. These days the artisan/craft distinction has been corrupted by advertising; it’s common to see signs about artisan bread, for example, when strictly speaking bread is produced by craftspeople – yeasty replicas made by hand every day. So if you prefer to think about writing as a craft, then focus on the commonality between the artisan and the craftsperson, that is, the development of highly refined and skilful processes.

Becoming a writing artisan takes continued practice. A writing artisan develops a rich repertoire of strategies for producing and refining writing. They build their writing muscles, and their flexibility, adaptability, dexterity and stamina. They equip themselves for the long research and writing journey ahead.

For the PhDer, learning to write means establishing routines for writing notes, summaries, journals and chunks for supervisors. It means taking time to try out writing in various styles, voices and forms. Working with description, quotations, with dialogue for instance benefit from experimentation. Testing out different approaches to anecdote, or writing with theory, means that you can choose which of your efforts seems to work best and why.

Sometimes you might get some help in building a writing practice. Perhaps the university might offer classes, writing workshops based around particular text types – journal articles and conference papers for instance. But more is required to build a sustainable routine and expertise. Generally, growing a writing practice is left to the individual PhDer. You have to design your own programme for acquiring expertise.

So what does this mean for you?

Well, if you take on board my three points – writing as a social practice, building connoisseur knowledge and an artisan repertoire of strategies – at the very start of the PhD, then you know you have to set aside regular time to work on your writing, as well as on your substantive topic. And given that the test of the PhD is the production of a persuasive, trustworthy well written and structured text, you also know this will be time well spent.

Photo by Clique Images on Unsplash