by The Thesis Whisperer: https://thesiswhisperer.com/2019/04/10/should-you-leave-your-phd-off-your-cv/

A couple of weeks ago I shared some of the research I have been doing with my colleagues Associate Professor Hanna Suominen and Dr Will Grant about recruiter’s attitudes to PhD graduates.

I recommend you read the previous post on anti-PhD attitudes before this one, but briefly: our research concerns recruiters, who are important gate keepers in the non-academic employment process. A recruiter might be the first person to read your resume and most of them do not have PhDs. In fact, some have very little experience or knowledge of the PhD process. You need to account for this fact when you enter the non-academic employment market.

|

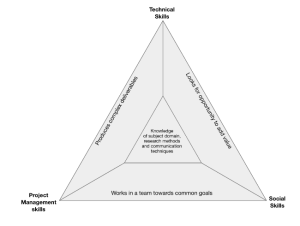

Model of professional skills required by non academic employers of researchers – from the research of Mewburn, Suominen and Grant (2018)

Recruiters are much more interested in your experience than your education and will not see the PhD as a reason to put you on a short list. While some recruiters see the PhD as clear evidence you are intelligent and dedicated, they might still actively exclude you from a short list on the grounds that the last PhD they hired did not turn out well. In my previous post I argued that a PhD positions you as a minority in the job market and you may face the kinds of discrimination that are routinely experienced by people of colour, older workers and those with disabilities.

After you read my previous post you might be tempted to leave your PhD off your CV altogether. Some people told me this strategy got them on the short list, but others said it made no difference. People who dropped the PhD had to account for the up to five year hole in their CV and usually did this by describing their PhD as a ‘large research project’ done inside the university. I think it’s important to bear in mind what I said in my previous post about what sort of activity counts as ‘work’ and how different experiences are valued. Recruiters think of the university as a very distinct kind of workplace and are often unconvinced that a PhD represents the right kind of experience.

If you want to minimise your status as a PhD holder, you don’t have to hide it completely; just move the education section further down so it’s not one of the first things recruiters read. As a research educator, it hurts my heart to think people have to actively hide their credentials and, to be honest, I’m not convinced it’s the right way to go. On the job market you still have many advantages over other people who do not have such highly developed skills in research and writing. The trick is to leverage the advantages of your PhD as best you can. Start by trying to understand what is going on in mind of the person reading your CV. Recognise and accept that some of the concerns recruiters and employers have are legitimate and make sure you address their concerns directly in your cover letter for the position.

Below I have listed some of the attitudes our research has uncovered and some ideas for how to counter these fears:

Employers are worried you can’t do the job that’s actually advertised

There’s a lot of talk about ‘transferable skills’, but I am not convinced there is such a thing. Take a deep breath and dwell for a moment with the idea that you have trained for a long time in a set of skills that are specific to academia and these skills – in their current form – might be of limited value outside of that context. Skills can’t directly be transferred, but they can be translated. You’ll need to demonstrate this translation has already occurred to any potential employer.

Writing is a good case in point. Just because you can write academic papers, or a 100,000 word dissertation, doesn’t mean you can do the kind of writing a non academic job requires. Recruiters know this and will not be impressed with the list of papers you sweated blood to produce. I have some sympathy with recruiters on this one. I recently advertised a job that did not require a PhD and people sent me CVs with reams of publications in areas like physics and biology. While I was impressed with the sheer number of papers, I did not ask for a research paper writer. I am well aware – as are most employers – that academic papers have very specific discipline conventions that may make them unreadable to the uninitiated. Looked at this way, a big list of research papers might make your considerable skills in writing look worse than they are!

Instead of a big list of publications, briefly tell your potential employer how many research papers you wrote and include a link to somewhere they can verify this information. Stop treating your CV as a kind of trophy cabinet and try to think about your writing skills from your potential employers point of view: what value add do your skills represent to them?

Have a look at the kind of writing on their website or publicly available company documents – and internal documents if you can get hold of them. Do you have evidence that you can do this kind of writing? If so, privilege this information over your list of research publications. If you can’t demonstrate you can write across genres, try unpacking the specialised PhD writing skill so your potential employer can understand how it applies to their needs. Don’t tell them you can do a literature review (a term not used outside of academia), explain that you are capable of ‘quickly distilling key information from a range of sources to inform others of the latest research developments’. Don’t tell them you can write compelling arguments, tell them you can use your writing skills ‘to influence key internal and external stakeholders’. Don’t tell them you can interpret data and develop theories, tell them you can ‘use evidence to explain a problem and convince others to take a specific course of action’.

I word of warning: don’t assume recruiters will buy your attempts to repackage your skill set: it is always better to show than tell. If you are serious about working outside of academia, seek out opportunities to use your skills in other contexts. Finally and most importantly: remember every piece of writing you send to a potential employees is a demonstration of your expertise. If you can’t write a short, compelling email, format a word document or avoid egregious spelling mistakes, you are doing yourself damage from the very beginning. Your employer is going to read hundreds of emails from you, so start how you mean to go on.

Employers are worried that you will work too slowly

Speed is important in a business setting. Recently, a friend who works at one of the big four consulting firms complained over lunch that he had plenty of money to commission academic research, but that he was unable to find any academics who could deliver research within a reasonable timeframe. It turned out the academics he contacted proposed a 9 month research project, but he wanted it done in six weeks. I have sympathy for the academics in this case: if they had 6 weeks to do research and nothing else they probably could deliver. I explained to my friend that nine months is actually a pretty short turn around time considering how much teaching and other administrative work must be done. He was unimpressed: ‘speedy’ clearly means something different in academia than it does in business.

You’ll need to account for this different conception of speed in your communications with potential employers. Remember non-academics have no idea about what is normal in your discipline. If you wrote a lot of papers compared to others doing a PhD, tell them that you are ‘x% more productive’ than others in your field. If you completed your PhD without needing any extensions: congratulations! Tell the potential employer that only 20% of people manage this feat.

If it took more than three years to do your PhD full time, an employer might question your ability to get things done. This sucks for people who had terrible supervision or difficult experimental results that caused their projects to run over time. You’ll have to find a way to explain the situation without sounding bitter – no one wants to work with someone who blames other people for problems (even if it’s true). Trouble with finances is a good, neutral reason to explain longer time frames. Explain you had to go part time to support yourself and emphasise the time management skills you gained from juggling study and work.

Employers are worried you will be bored and run back to academia as soon as you have the chance

Recruiters told us they were worried that PhD graduates would be a flight risk; liable to run back to the academy at the first opportunity. They know that some PhD graduates look at industry jobs as sloppy seconds. Now sit with this idea for a moment: are they entirely wrong?

You might tell yourself you are sick of academia – and there’s plenty not to like – but if that dream job came up, you applied and by some miracle got it … would you REALLY turn it down? If you can honestly answer yes, you are ready to leave. If not, you might need to see if you can follow your academic dream for a bit longer. Most recruiters are pretty good at their jobs and will sense if you are not committed to the idea of the ‘outside’.

You might be totally over academia, but convincing a non-academic employer – without sounding bitter – is easier said than done. I think the best strategy is to be honest and tell them why you applied for that job in particular. Be very specific: “I have done lots of interviews during my PhD and I’m interested in how these can be used to make products and services better”; “I prefer to work in teams and this job offers me opportunities that are not possible in academia” are both better answers than “there were no opportunities in academia for me”.

Employers think your expertise is too specialised

I did my PhD on hand gestures in architecture teaching. Clearly I don’t do anything like that now. A colleague of mine has a PhD in marsupial reproduction and is a now a really amazing business development manager. The idea that a PhD is destiny is a very outdated notion to us, but is it really? Let’s dwell with this idea for a moment and think about how the PhD process might force us to be too narrow.

Recruiters told me they prefer to see a masters degree on CVs as it suggests someone has research skills, but is not too specialised. There is some truth in this. I often talk to candidates in anthropology and social science who do not have any skills in quantitative analysis and are almost phobic of numbers. Likewise I talk to scientists who seem to lack basic skills in representing and talking about data, while displaying dazzling virtuosity in one specific, highly complex stochastic analysis types. The PhD does force you to specialise to the needs to your topic – which is ok if you are coming off an existing broad skill set, but many of us do not have this luxury.

During your PhD you could take short courses and broaden yourself out, but most people don’t even explore these options. I am no exception. I remember one of my PhD colleagues sweating over a course she took in statistics as an extra in her PhD, even though she didn’t need statistics for her topic. I thought this was a waste of time back then, now I think she was really smart. I struggled to learn statistics later because every job I’ve had in academia requires at least basic knowledge of how to process this kind of data. I often wish I took that stupid course with Paula.

Take a good look at your CV and ask yourself a hard question: are you too specialised? If so, do something about it – if you’re still inside the university, accessing extra courses is much cheaper than it will be when you finish. If not, what other jobs and experiences can you draw on to demonstrate a broader skill set? If every example of a skill set that you give an employer comes from your PhD, you make yourself look much more narrow than you are. You’ll need to think about how you are going to demonstrate important skills in team work too: our research shows this is one of the top priorities for employers. The PhD is the epitome of a solo pursuit, so you may not have anything you can point to in your university career that demonstrates teamwork, but what about before that?

All your work experience is potentially valid in the hiring process. When I went for my current job at ANU the interview panel asked me how I planned to be a manager when I listed no managerial experience on my resume. I realised I left out all the work I did managing both a book store and a record store (remember those?) in the 1990s when I took a break from study. I reached back into those experiences to explain to the panel the size of team I managed in those shops, the business processes I implemented when computers first appeared on site and the difficulties of managing employees who were dealing drugs under the counter … Jokingly I said “So if the police turn up, I’m your woman!”. The panel were much more interested in this experience than my PhD and to this day I wonder if those outrageous stories from retail are the real reason I got the job!

Employers think you will expect high wages

Most PhD students laugh out loud when I tell them this is a real employer fear. I’m sure you are more than ready to earn a proper salary. However, be careful not to over value yourself when you scan the available jobs. You are starting over in a new area and will need to go low and aim high. It’s a bit of a goldilocks dilemma though: too low and you look ‘over qualified’; too high and you look inexperienced. Judging by the discussions I’ve had with PhD graduates over the last couple of weeks, it can feel a bit ‘damned if you do, damned if you don’t’. If you go in too low, employers might think you will get bored.

I don’t know the way out of this catch-22 dilemma except to say that you’ll have to stick at it, perhaps longer than you would like. This is the time I should again highlight the value of doing some pro-bono work and networking. The idea of doing free work is to ‘get your feet wet’ and start to meet people who can speak for you being a bright spark who should be given a chance. For what it’s worth: this strategy has always worked for me. I have never once got a job by applying to a job advertisement ‘cold’. All my career success, as an architect and then an academic, has been the result of showing people what I am like to work with. People tend to love the way I work, so I have little trouble getting promoted internally, even if it’s a bit difficult getting my foot in the door – but this is a post for another time as I just hit triple my usual word limit… clearly I have a lot to say. Maybe it’s time to write that book!

I hope this post helps you start to think about positioning yourself and your CV. What do you think? Have you tried any of these techniques? Do you have any more advice to offer? Interested to hear about your experiences in the comments.

I have weaved in much that I learned from talking to PhD graduates on the blog, Facebook and Twitter into to my advice on hiding the PhD on your CV. I usually like to give direct credit for advice, but in this case I have chosen to leave off specific names because I don’t want to ‘out’ anyone for ‘devious’ behaviour. I sincerely appreciate these conversations: thank you. I am lucky the Thesis Whisperer is blessed with a highly intelligent and generous community!

Previous posts on our employability research

Our research papers

No comments:

Post a Comment