by Hannah Forsyth, The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/universities-and-government-need-to-rethink-their-relationship-with-each-other-before-its-too-late-139963

I’m reading Thomas Carlyle’s poetic classic, The French Revolution, published in 1837. It occurred to me that the historical narrative of Australian universities and their relationship to government is like that revolution, but in reverse.

Carlyle summarised the goal of the French Revolution with the refrain “victorious analysis”. This was the foundation of Australia’s modern, rational system of government, achieved with universities. It was a triumph that turned out to be deeply flawed, as we will see.

Reversing the revolutionary process, in recent years universities have descended into the kind of aristocratic excess Carlyle described in pre-revolutionary France. This leaves a large scholarly workforce facing (this is Carlyle again) “an indubitable scarcity of bread”.

It is an admittedly dubious historical parallel, but it helps us understand something of the relationship of higher education to Australian politics, and the mess we now face.

The foundation of the Australian university

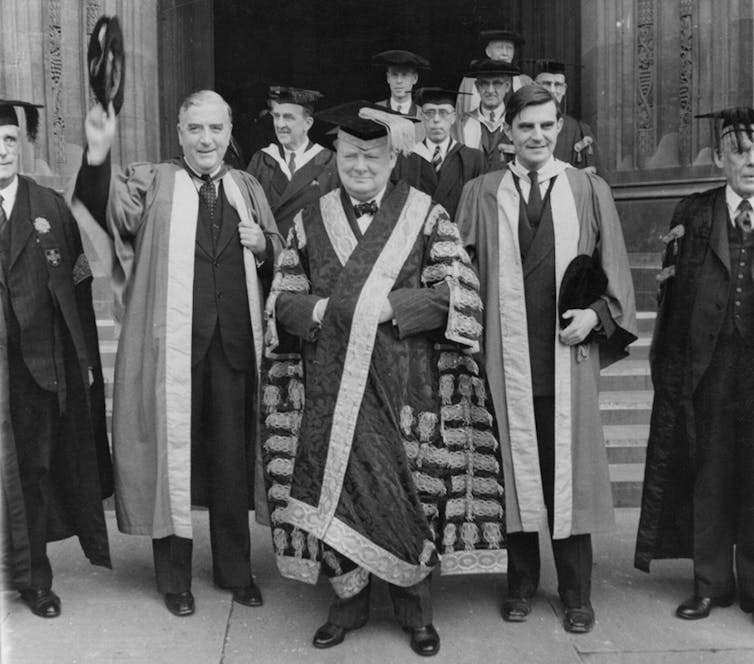

|

| W.C.Wentworth. State Library of NSW |

In the mid-19th century, when Australians decided they wanted to govern themselves, political leaders knew they needed a university. Politician and university founder W.C. Wentworth went so far as to argue that self-government in New South Wales – the kind of modern, rational government increasingly in vogue since the French Revolution – would be “useless” without higher education.

In Carlyle’s more flowery language (citing Plato’s Republic): Australia had no aristocracy to overthrow and the founders of our first governments sought a basis for rule that did not rest on inherited position. University graduates, Wentworth believed, were needed to “enlighten the mind, to refine the understanding, to elevate the soul of our fellow men”. They were also needed to train men – and, shortly, women – to fill “the high offices of state”.

Kings can become philosophers; or else philosophers Kings. Let but Society be once rightly constituted, by victorious Analysis.

This merit-based elite – which some of Wentworth’s contemporaries ridiculed as a “bunyip aristocracy” – constituted the emerging professional class. Their work as medical practitioners, lawyers, clergy, teachers, charity workers, engineers and politicians was to guide this “rightly constituted” society.

Such modern, rational governments relied on the kinds of knowledge that a university pursued. “Victorious analysis” guided Australian governments through rabbit plagues and conquered parasites and diseases that threatened food supply and human health.

But it also steered the conquest of Aboriginal lands with knowledge of geology, geography, anthropology and agriculture. And it equipped generations of teachers and clergy with the wealth that was Western history, literature and philosophy – embedded in a racialised, moral superiority.

It was not perfect. Indeed, in many ways this “victorious analysis” was downright harmful.

The kind of knowledge the university produced helped build the nation, but it did so by also developing and reinforcing ideas that expropriated Indigenous land and oppressed people of colour. It built and encouraged ideas that determined a human’s worth on the basis of race, gender and sexuality. Universities and the governments they supported structured a so-called “rational” world that extracted value from some people and concentrated it among themselves.

Exposing the flaw in ‘victorious analysis’

By the second world war, some of these problems were becoming evident worldwide. In that war, the same “victorious analysis” combined with political regimes that sought to use “rational” knowledge to commit atrocities, even genocide, and demolish cities full of civilians.

It was at work when Nazi doctor Josef Mengele compared the effects of cruel experiments on twins at Auschwitz. Through those unspeakable experiments on 1,500 sets of twins, only 200 survived.

The dangers of aligning scholarly knowledge with political regimes was further exposed when, in the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin dismissed, imprisoned or executed thousands of biologists. The reality that their knowledge may have helped prevent a tragic famine was not more important to Stalin than that their understanding of genetics contradicted government doctrine.

Democratic regimes were not immune. “Victorious analysis” led to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. When news of those horrors filtered through, Western democracies saw the problem engendered by the relationship between modern, rational government and scholarly research.

Protecting the independence of scholarship

This did not mean governments sought to dismantle or undermine universities. On the contrary, Australian governments, like most others, invested in them further. However, care was taken, in Australia as elsewhere, to increasingly protect universities from political interference.

At this moment, Nobel-prize-winning author Herman Hesse had his character Joseph Knecht express the significance of scholarly independence in his novel The Glass Bead Game, published in 1943. Describing an age where rulers “determined the sum of two and two” and scholars capitulated (and lost their self-respect), protested (and died) or learned the art of silence (merely going hungry), Hesse’s character concluded that scholarship and politics must not mix:

The scholar who knowingly speaks, writes or teaches falsehood, who knowingly supports lies and deceptions, not only violates organic principles. He also, no matter how things may seem at the given moment, does his people a grave disservice. He corrupts its air and soil, its food and drink; he poisons its thinking and its laws, and he gives comfort and aid to all the hostile, evil forces that threaten the nation with annihilation. The Castalian [scholar], therefore, should not become a politician.

These sentiments were not confined to fiction. As the Commonwealth government sought to support the expansion of higher education – a tricky task, since education was and is the responsibility of Australia’s states – they were conscious of the contradictions required of them.

The 1957 Murray Report, arguably the founding document for the modern university in Australia, pointed to exactly this.

Here is one of the most valuable services which a university, as an independent community of scholars and inquirers, can perform for its country and for the world. The public, and even statesmen, are human enough to be restive or angry from time to time, when perhaps at inconvenient moments the scientist or scholar uses the licence which the academic freedom of universities allows him, and brings us all back to a consideration of the true evidence and what it may be taken to prove …… No nation in its senses wishes to make itself prone to self-delusion, or to deceit by other nations; and a good university is the best guarantee that mankind can have that somebody, whatever the circumstances, will continue to seek the truth and to make it known. Any free country welcomes this and expects this service of its universities.

On the basis of this report, Prime Minister Robert Menzies instigated what is likely the most generous funding Australian universities have ever seen.

He was building on work that Labor did during the war, establishing the Universities Commission and implementing a funding scheme that helped universities build new infrastructure.

The clashes produced by the dual need for scholarly independence and democratic accountability emerged early. “What I am asking,” argued the vice-chancellor at Sydney University in 1943, “is that you give us the money and be done with it.”

The government bureaucrat replied:

It is a large sum of money and when the Government says ‘We gave this subsidy, did the universities find it all right?’, we must be able to say something more than just ‘Trust the Universities’.

Solutions and compromises were negotiated, though the original problems of “victorious analysis” remained.

Contesting the moral foundation of the university

By the 1970s, students and academics began to point out that this rational, supposedly objective system of knowledge veiled ideologies. This was not avoidable, they argued, and so the solution was to seek knowledge systems that were inclusive and decolonising, rather than those that supported established systems of inequality.

Under Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s policy of free public education, the university sector expanded, seeking innovative and inclusive methods of learning and teaching.

In retrospect, this disruption in the universities marked a shift in the moral focus of the professional class. Where university graduates were originally central to the colonial project and capitalist expansion, they now turned their moral efforts towards moderating both.

This put them at odds with the political and managerial classes with whom the professional class, in the mid-20th century, had managed the entire world, through institutions like the World Health Organisation.

Rise of the managerial elite

But now the professional class split from the managerial class. Using radical student critiques of old moral codes as a springboard, in the 1980s the managerial class sought freedom from traditional moral constraints, which they believed also constrained capitalist growth.

This was more than a culture war: it was conflict over the moral foundation – and thus the control – of the economy. It was a kind of class struggle between a changing professional class and a newly separate, managerial class.

New values infused government and university leadership alike, forging what became known as neoliberalism. By the mid-1980s, “victorious analysis” was no longer the basis of government. Yet, ironically, government and economy alike relied on universities more than ever. Innovation was often key to profitability, and the changing global economy required ever more white-collar workers: university graduates.

In 1987, Labor Education and Training Minister John Dawkins led a review of higher education that sought to shift the entire university and college sector from “victorious analysis” to economic asset. Rather than considering the university as a moral institution, it would now be an economic one. An international student “export” market was a key component of 1980s reforms. So too, was massive expansion in the enrolment of Australian students.

But that professional class – which included academics, journalists and teachers, in influential roles – could clearly not be trusted to prioritise capitalist expansion over moral reform.

Transformations in higher education, then, wrested institutions from academic control. Over the following two decades, management of universities became a professional pathway almost entirely distinct from the pursuit of scholarship.

We must not romanticise universities run by academics under the old conditions of “victorious analysis”. As we have seen, this did a great deal of harm. But the fact that the system needed to change need not imply a managerialist solution.

Steered by government policy, an expensive managerialist epidemic infected the universities. Every year, millions of dollars in salaries alone propped up a this new “aristocracy”, a managerial elite.

Leaders assured us this was the best way to manage these growing and complex institutions. But, instead, managers encouraged one another to game the government’s funding system to achieve their KPIs (and earn spectacular bonuses). The cost has been a failure to invest in good universities that are sustainable in the long term.

Failure to build a good university sector

Looking at the state of the university sector now, we surely cannot consider the managerial salary bill to be money well spent. The present crisis was exacerbated by COVID-19 but was not unexpected.

University leaders were repeatedly warned of financial risks, of threats to the university’s legitimacy (and thus community and political support). They have also been reminded continually of their moral responsibility as public institutions. And yet, like Carlyle’s King Louis XV, they have pilfered resources that were “sufficient not to conquer Flanders, but the patience of the world”.

Like that French aristocracy, the university sector in Australia has been teetering on the edge of ruin for decades. In some ways it is astonishing it has taken so long to tip over. Carlyle, on pre-revolutionary France, noted that:

[…] it is singular how long the rotten will hold together, provided you do not handle it roughly.

Australian universities have long teetered – or, worse, arrogantly swaggered – on a precarious foundation. Their precarity goes beyond their over-reliance on international student fees and management’s tiresome reprises of what Geoff Sharrock calls “yesterday’s logic”.

All of this – the education of young people, the medical research we’ve all been sitting at home waiting to be done, our entire stock of knowledge of history, mathematics, robotics, climate science – sits atop a 93,000-strong workforce of casual academics on starvation wages. It is these academics who will probably be out of work within the month.

They will likely be followed by thousands of their better-paid, but still overworked, teaching and researching colleagues, then thousands of the indispensable workers who throughout the pandemic have kept the technology running, the exams timetabled, library resources accessible, the payroll delivered, and who have cared for troubled or confused students.

A good university sector would look at 100,000 very clever, highly qualified and extremely hard-working scholars and see a valuable resource.

A good government would work with them.

The job of building a good university out of the system we have inherited from history is a more revolutionary task. It is one we all need to share.

No comments:

Post a Comment