by Pat Thomson, Patter: https://patthomson.net/2019/03/25/revise-and-resubmit/

Yep. Those dreaded words when you get the email back from the journal. R and R. Anything but Rest and Relaxation. Groan. In essence, the message says We have considered your paper and we have decided that – well it’s just not going to cut it. At this point. However, we see enough in it to give you another shot. But only one. And (to steal Ru Paul’s words) Don’t **** it up.

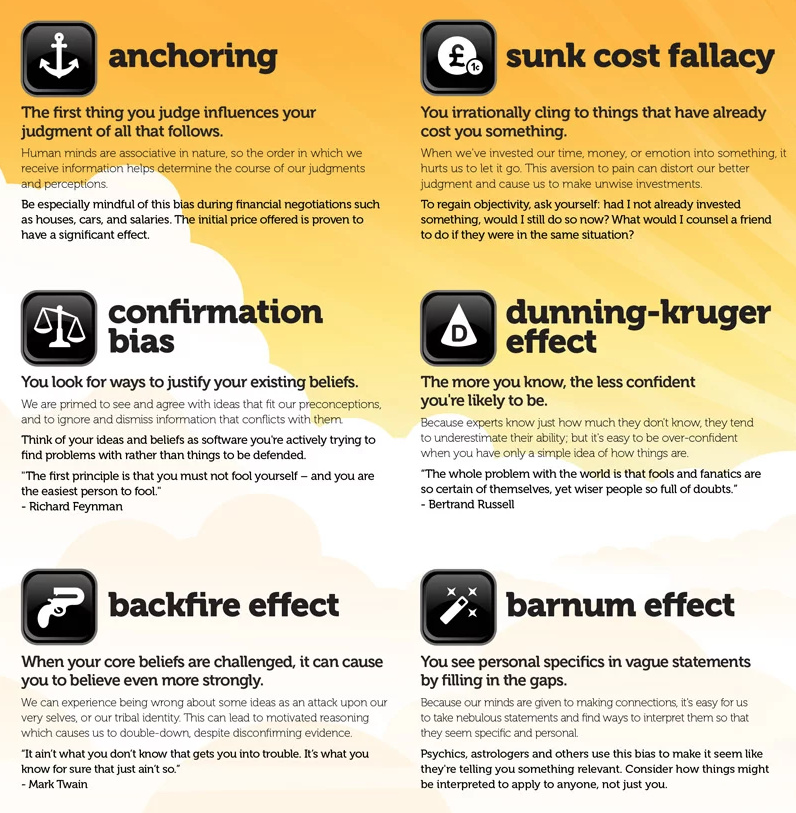

Now the usual advice – and I give it myself – is that when you’re working out what corrections to make it’s helpful to go through the reviewers’ comments and put them in a two column table. You put what the reviewer said in one column and what you did in the other. As in …

| Add more detail to methods | I added four sentences about sampling and two about analysis |

| Use more literature particularly look at x,y,z | Added xyz to literatures section |

Now the make-a-table approach is pretty well always going to work for minor corrections and probably even for the bigger major corrections. But it might not be enough for an R and R.

The key work in R and R is REVISE – re-vision, re-imagine, re-think. This may well be more than simply adding in a few sentences here or there or a new section. An R and R not always going to be a ‘tinkering around’ leaving most of the paper intact. Just adding and deleting a few things is a correction, not a re-imagining. In fact, most of the time, when reviewers recommend R and R they are looking for some pretty big changes. Gah – it’s likely to be a pretty substantial re-write.

It’s tough to front up to a paper and try to rethink it. To start again. To try to work out how it might be different. That’s because we get attached to our words. We may even like the paper that we wrote and find it pretty galling that the reviewers didn’t. We may want to try to get away with the least possible number of corrections. We may seriously not want to even consider the possibility that what we are being asked to do is a lot of extra hard work. That’s natural. But that is what we are being asked to consider.

And here a pause. Just to say that I speak here from experience. And lots of it. In just the last twelve months, my colleagues and I have had two R and Rs. Other papers went through with minor changes, but, yes, we had two papers where we were told R and R. It happens to all of us.

Our problems weren’t to do with the actual writing of the paper but what we were writing about. The reviewers of the particular journals just didn’t find the arguments we were making particularly interesting or persuasive. Now, it wasn’t all bad. Writing the papers had been very useful for our research project – they really helped to advance our analysis. But they just weren’t suited to the journals we wanted to publish in.

So, when faced with the two the R and Rs, we had choices – take the papers as they were to other journals, give up on the papers altogether, or try to do enough tweaks to get past the reviewers. Or – we could rethink the papers. Yes, rethink. Go back to the beginning and start over.

In both cases, that’s what we did. We went back to the beginning.

One paper didn’t require as much rethinking as the other. Paper A reviewers suggested some new literatures for us to read. We read them and then constructed a somewhat different argument – more nuanced perhaps than the one we had originally submitted. The title of the paper stayed the same, but there was a new abstract, a new theoretical discussion which incorporated the new literatures, a new thread of analysis and a new conclusion.

The second paper, paper B, had a much more dramatic change. The reviewers didn’t seem to get our argument and found the topic and our empirical work not particularly interesting. They seemed to say that our theorisation was pretty incomprehensible.Or light weight. One or the other. But potentially interesting. So we switched the focus of the paper and it became about the theoretical development since that was what seemed to be of interest as well as at issue. We used our empirical material – which we love – to show how the theoretical work might be done. The paper ended up with a new title, abstract and argument. It was almost entirely rewritten with only the methods section and some of the empirical reporting carried over.

While we might be able to explain the changes made to paper A through a table, paper B wouldn’t fit in a table at all. The changes were holistic. We had taken a cue from the reviewers’ comments and re-imagined and re-designed the lot. Holus-bolus. It was a new paper born from the remains of the first one.

I guess you want to know if the papers got published once the R and Rs were done. Yes. Both are now in print. But neither of them would be if we hadn’t been prepared to just go with where the rethinking took us. If we weren’t ready to make whatever changes followed on from the new literatures (paper A) or whatever resulted from trying to explain our theoretical development in sufficient detail for it to be understood. We were ready and able in both cases for a complete and comprehensive overhaul. And Paper B was just this – a complete and total reworking.

There’s a clear and obvious moral to this story. And it’s that R and R may mean more than a few additions and deletions. It often requires you to have the courage to say – wrong journal – or the courage to say Oh. I need to put the first version to one side and try to understand the reviewers’ overall message, not just the individual points they are making along the way. I just have to suck it up.

So some questions to help in this R and R revisioning process – What am I being told about the paper, what’s the reviewers’ story about my paper, where do the reviewers actually think the problem is? The structure of the paper? The argument isn’t evidenced? If I had read some different literatures I’d potentially change my argument? The theory doesn’t fit or isn’t well developed? The paper doesn’t fit with the interests of the journal and I need to shift focus if I want to be published here?

These kinds of questions orient you to consider the paper in its entirety. Take a helicopter view. See the paper in the landscape of the journal and its readers. Adopt an evaluative stance to your own work.

But ultimately R and R is a question of having the will to chuck the paper up in the air and see where it lands. And this might be a case of singing to yourself …

There once was a writer called Dr Finnegan

Wrote a paper they thought’d get in again

Got an R and R back and had to bin again

Poor old Dr Finnegan. … Begin again.