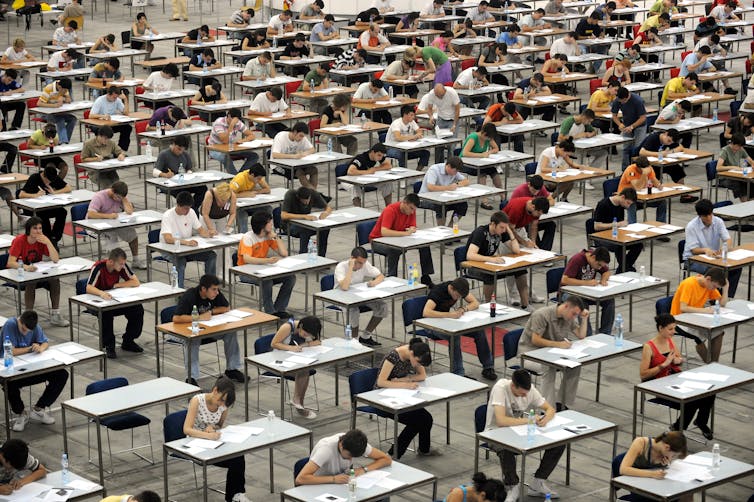

This shift was heralded by the introduction of a whole host of performance indicators across the global higher education sector – which has become increasingly “gamified” with points and rankings, and winners and losers. And just as universities play against each other for the “top spots” on league tables, students are also taught to compete to be the most “employable”.

For universities the stakes in the game of the higher education market are high. But for students and academics, the stakes of a life transformed into a competitive game can be highly problematic.

More students are dropping out of university because of mental health problems. And the mental health of academics is also suffering more than ever before. One recent survey found that 43% of academic staff exhibited symptoms of at least one mild mental disorder, with increased workloads, and pressures surrounding the job primarily to blame.

Making knowledge production into a game also puts academics in competition with each other, as research is being measured mainly by who publishes first and in the “best” journals – which actually slows the progress and sharing of knowledge.

A game to be won

Framing education (and society) as a zero-sum game can be directly tracked back to the 19th-century pseudoscience of “Social Darwinism” and the eugenics movement. This reflected a view of life as a “gladiatorial struggle”, which has been dominant ever since – even when disproved by science.

So despite all the evidence which shows the importance of working together and cooperation, many people still believe that competition is the most efficient way to organise society.

This has led to the idea that education has to be competitive and only the best will win. And in terms of higher education, the myth of competition is perpetuated by a vision of education not as an element of the common good, but as individual, competitive advantage – a ticket to the top.

The consequences of gaming

Student attainment, as measured by student “outcomes” and graduate employment after university, is now fundamental to university rankings, which in turn influences student recruitment.

To avoid being the “losers” in these games, both students and lecturers are put under an extreme amount of pressure to relentlessly focus on outcomes instead of processes. This in turn impacts on another key factor, student satisfaction, as measured by linear scores in the National Student Survey.

Research has shown that the need to top the scoreboard pushes academics into providing entertainment and services to the “students as customers” instead of challenging them to think critically.

Think about the players

My research in the field of global higher education has shown me how entrenched this global “game” has become. But my research on playful learning has also shown me a possible way out.

Play scholar Bernard DeKoven highlighted two different ways of forming a community around any game: “game community” and “play community”.

The game community is all about winning: the game comes first, it is unchangeable, and decides who is a worthy player and who is cast out. This is what we are seeing now, both in education and in society as a whole. The play community is the opposite. It’s about the involvement of the players. It’s the players who decide if a game is worth playing as it is, or if it would be more inclusive to change it.

Over the next few months I will run a series of workshops, with students, staff and partners all around the world, that will look into “unpacking” the games we play. The hope is that these sessions should help to provide solutions and raise some important questions for the sector, directly from the “players”.

And given that a recent poll of almost 38,000 UK students suggested that rates of psychological distress and illness are on the rise in universities, it is clear the sector desperately needs to reclaim its play community – and create an alternative, cooperative and inclusive “playground” sooner rather than later.

Luca Morini, Research Associate - Education and Media, Coventry University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment